Steep Learning Curves Are Not What You Think

Could Mastering "Good Enough" Be the Key to a More Fulfilling Life?

We’ve all heard the warning “oh that has a steep learning curve” about something that’s difficult to learn. As it turns out, the exact opposite is true—the steeper the curve, the faster the learning. The term “steep learning curve” is a deeply rooted cultural misnomer, and it drives me crazy every time I hear it.

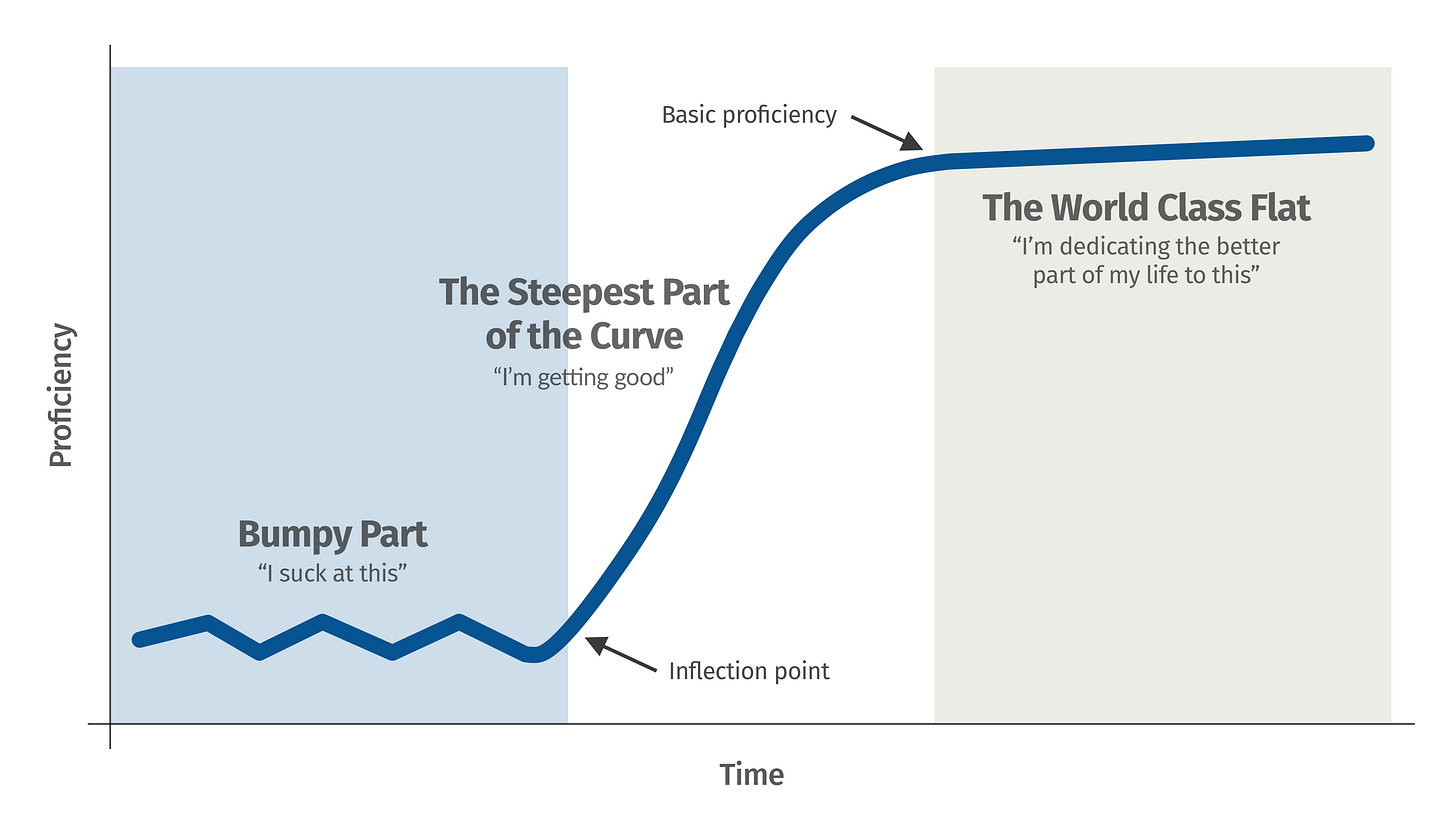

Real learning curves follow an s-shaped pattern where the vertical axis measures skill proficiency and the horizontal axis represents time as shown in the chart below. This s-shaped pattern for human learning has been replicated countless times in scientific studies measuring everything from Croatian Harvest Machine Operators to British Ultrasound Trainees to New Zealander Colonoscopists.[i][ii][iii] The s-shaped learning curve is not controversial; it simply illustrates the way humans learn new skills over time.

You’ve likely experienced speeding up a steep learning curve yourself, when you learned to ride a bicycle. I taught my three kids to ride a bike and the day those training wheels come off, there is a lot of fear coupled with a complete lack of understanding of how this all works. This is a time when some kids say they don’t want to learn how to ride, or they just want to keep the training wheels on. What they are experiencing is the seemingly endless Bumpy Part of the learning curve as shown above.

After minutes, days, or even weeks of bumpy trial, the bike learner hits an inflection point, the moment they start pedaling forward with force while simultaneously using the handlebars for balance. Aha! The fun part! From that “inflection point” to confidently riding around the neighborhood usually takes less than an hour. Those few minutes are the Steepest Part of the learning curve, when something “clicks,” and learning is easiest.

Some point soon after getting through the Steepest Part, most people stop getting significantly better at riding a bike. Yet they are proficient enough to enjoy riding for the rest of their lives. A tiny percent of those bike riders will go on to ride in the Tour de France or do amazing tricks on BMX bikes. Those are the people who take the long journey on the “World Class Flat” and may spend 10,000 hours or more perfecting their skill.

But is there an advantage for the “rest of us” who don’t go far on the “World Class Flat?” The book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World argues that getting pretty good at a lot of things has many benefits, among them better adaptability, improved problem solving, and increased creativity. Perhaps most importantly, leveling off at proficiency in one skill gives you time to learn many other skills—to become a jack-of-all-trades or generalist.

As we’ll see in future newsletters, being open to getting “good enough” at a broad range of skills can be a career change enabler, help you overcome seemingly impossible obstacles, or simply bring you joy.

[i] Purfürst, Frank Thomas. “Learning Curves of Harvester Operators,” December 20, 2010. https://hrcak.srce.hr/63720.

[ii] Mullaney, P. J. “Qualitative Ultrasound Training: Defining the Learning Curve.” Clinical Radiology 74, no. 4 (April 1, 2019): 327.e7-327.e19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2018.12.018.

[iii] Parry, Bryan R., and Sheila Williams. “COMPETENCY AND THE COLONOSCOPIST a LEARNING CURVE.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery 61, no. 6 (June 1, 1991): 419–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.1991.tb00254.x.